Covid-19 (or coronavirus) is a virus that causes severe respiratory damage that can be fatal in some cases. The outbreak originated in China at the end of 2019, rapidly turning into a pandemic and affecting several countries simultaneously where more than 100,000 have been infected. In situations of massive risk, States are obliged to offer timely information so that people can make decisions and know how to prevent and respond most properly.

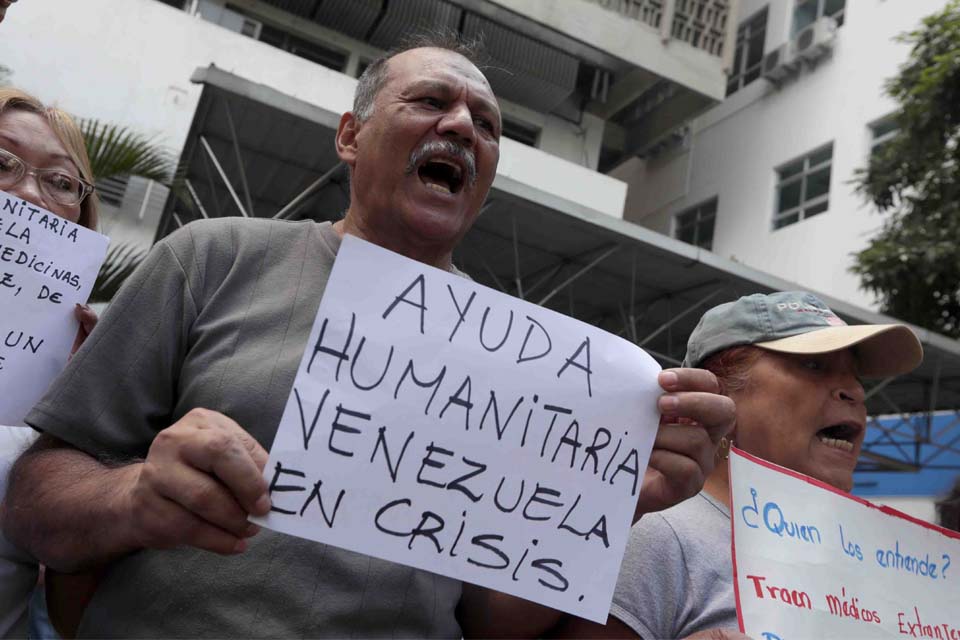

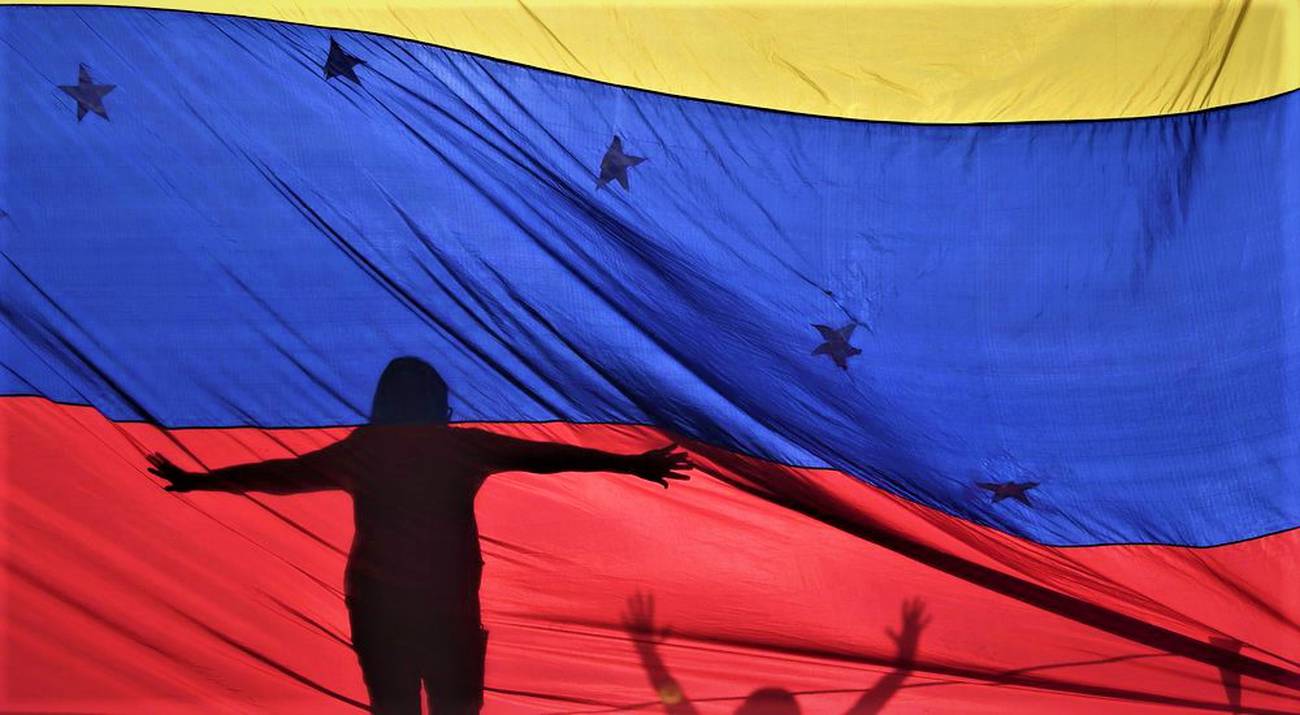

Since January, when the existence of the Covid-19 was announced, diffuse information and rumors began to circulate, mainly through the internet, regarding symptoms, forms of infection, prevention mechanisms, and the mortality rate, creating great disinformation about the virus. In the case of Venezuela, the situation is accentuated by indirect threats and restrictions imposed by the national government, which, far from dispelling rumors and generating certainties, increase uncertainty due to the lack of official information.

Official versions

On February 27, Nicolás Maduro established the Permanent Commission for the Monitoring and Control of Coronavirus, chaired by Delcy Rodríguez. In the same speech, Maduro announced the launch of a campaign to raise awareness about coronavirus and how to prevent it “in homes, schools, factories, in the workplace, and on the streets.” He also assured that the Venezuelan health system is in a position to face the virus, which he described as an “attack”.

On March 8, the Commission made a public statement in which they did not admit questions from the press and where Delcy Rodríguez assured that “happily there is no occurrence of the coronavirus” in Venezuela while reporting that there is “very strict surveillance at all access points to our country.” In the broadcast by Venezolana de Televisión, Rodríguez maintained that the Ministry of Popular Power for Health distributed the clinical action protocol to all centers, both public and private, highlighting the articulation between the two health systems, in coordination with the Infectious Diseases Center of the National Institute of Hygiene, the entity in charge of diagnoses nationwide.

The Minister of Health, Carlos Alvarado, asserted on several occasions that the Venezuelan public health system is in a position to cope with the arrival of the coronavirus, without offering further details, and that in the absence of confirmed cases they are working on prevention campaigns. The Ministry released a list of 45 “sentinel” health centers, which are staffed and trained to receive patients with the disease.

On March 13, the government admitted the existence of the first two confirmed cases. That day Maduro declared a state of national alarm, which implied the suspension of classes at all levels and the prohibition of using public transportation without facial protection. Despite being a prerogative of the Executive Power, the declaration of a state of emergency requires two constitutional conditions to enjoy legitimacy: to be approved in the Council of Ministers and to be published in the Official Gazette. However, to this day the document is not of public domain.

A day later, on March 14, Jorge Rodríguez confirmed eight more cases and flights from the Dominican Republic and Panama were suspended for 30 days. On that occasion, Rodríguez declared that two cases were of local transmission.

On March 15, Maduro announced the detection of seven more cases, with a total of 17 verified. He announced a collective quarantine in force from the following day, including the suspension of work and educational activities, except food distribution, health, transportation, and security. On the night of March 16, the number rose to 33, with 16 new cases. On this occasion, Maduro indicated that all the cases were people who came from Europe and Colombia, although two days before there were two official cases of local contagion. 18 of the infected were women and 15 men.

The Official Gazette containing the declaration of a state of emergency was published on March 17, four days after its de facto entry into force and dated March 13. Three cases were added and the use of the metro system and railways was allowed only for those working in exceptional areas: health, transportation, telecommunications, and basic services. On March 19, six cases were confirmed with a total of 42 people infected in seven days.

Although government officials offered statements about the pandemic on different occasions, details of the evaluation of potential cases or the situation of the patients diagnosed remain undisclosed; the generality and repetition of information detract from the timely and updated character that is needed in a critical context, which contributes to the existing opacity around the issue in Venezuela.

Retaliation for reporting or commenting

In mid-February, violations of freedom of expression began to be registered, linked to the dissemination of news and opinions about the Covid-19 virus in Venezuela. To date, 18 cases have been recorded, with a total of 22 victims, including 10 journalists, five health workers, three media outlets, three photojournalists and a website. Regarding the number of violations, there were seven censures, seven arrests, six intimidations, four threats, three judicial harassments, two administrative restrictions, two verbal harassments, and one assault.

On February 21, journalist Gregoria Díaz published information on her Twitter account about a patient with flu symptoms who had been admitted to the Military Hospital of Maracay, where studies were carried out to rule out the virus. After the publication, the mayor of Mariño municipality, Joana Sánchez, harassed the journalist through social networks, an action that was replicated from anonymous accounts akin to the ruling party.

The instigation by the state officials is not limited to cyberspace. On March 9, the Governor of Zulia state, Omar Prieto, threatened the Director of Graduate Medicine of the University of Zulia (LUZ), Freddy Pachano after he made an alert about possible cases of coronavirus in the city of Maracaibo. The threats were made during a press conference, where he assured that the General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (DGCIM) would be in charge of investigating Dr. Pachano’s statements.

During these acts of harassment against anyone offering information or expressing his opinions on the situation, the public authorities did not report any potential Covid-19 cases under study. However, on March 10, in broadcast for the celebration of Medical Doctors’ Day in the country, Nicolás Maduro notified the dismissal of some 20 suspected cases, which were not officially accounted for in the previous days. Two days later, he indicated that “about 30 cases arrived nationwide in the past 3 weeks.”

After Maduro publicly admitted the detection of Covid-19 cases in Venezuelan territory, the restrictions escalated, significantly hindering the coverage of the events concerning the pandemic. Limitations worsened after the collective quarantine was decreed.

Such was the case of the union leader, Dr. Julio Molino, who was arrested on March 17 by officers of the Bolivarian National Guard (GNB) after he denounced, in the company of Carlos Carmona and Maglis Mendoza, the situation of the health system in Monagas. After Molino’s arrest, officers from the Anti-Extortion and Kidnapping Command (Conas) began looking for Carmona and Mendoza. Molino was put under house arrest and was charged with “incitement to hatred”, “incitement to panic”, and “terrorizing the community”.

Journalist Mariana de Barros 9 reported on March 16 that officials from the Bolivarian National Guard (GNB) prevented her from entering the city of Caracas, as a consequence of the measures implemented. Although she showed her card and the video of Minister Padrino López exempting the media from quarantine, the GNB told Barros had to go back since she was not exempt from the measure.

The responsibility to inform

Access to public information in Venezuela is an exception. The government frequently denies information, making opacity a state policy. The lack of information on public management and its consequences affects the relevance and efficiency of programs and services linked to basic needs such as access to drinking water, electricity and domestic gas. In a context where the institutional framework does not offer guarantees for human rights, the silence of the Public Power tries to hide not only its deficiencies but its responsibility in a structural crisis.

The National Constitution establishes that citizens have the right to information on the part of the public administration, and recognizes the right to appeal to any authority and obtain a timely and adequate response. However, 97 percent of the 279 requests for information made by Espacio Público (Public Space) between 2016 and 2018, mostly related to water supply, citizen security, and the right to housing remains answered. This tendency to opacity includes health issues.

In 2014, the Ministry of Health stopped publishing epidemiological bulletins, weekly reports on the state of communicable diseases that act as mechanisms of surveillance, control, and prevention. Three years later the minister was dismissed after the dissemination of bulletins for 2016 and 2017. The data showed increases in infant mortality as well as in cases of malaria and diphtheria. To date, reports from previous years and the current period have not yet been published.

The Justice system validates practices and measures that promote opacity. After a complaint filed against the Ministry for the lack of response on the budget allocated to the health sector, the country’s highest court described the request as “abusive”, considering that it hinders the normal operation of the public administration by unnecessarily overloading it. Contrary to what is established in national legislation, the Venezuelan state does not consider access to information a right and a priority.

Given the serious restrictions, the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights recommended the Venezuelan State to adopt measures to guarantee free access to information on processes related to public administration, make effective mechanisms of accountability, and establish functional schemes for the dissemination of information related to social programs and indicators on economic and social rights, including health.

28 out of 35 requests for information made in 2019 by Espacio Público were not answered. Two of them were inadequately answered. One from the Red Cross on the distribution of humanitarian aid was only referred to a website. The second was sent from the University Hospital concerning the effects of January 12, 2019, blackout. Authorities asked the medical center to show the constitutive act of the organization, which is not a legal requirement to access information.

A policy of opacity affects the guarantees of fundamental rights. For example, if the number of people infected with malaria is not known, it is not possible to establish effective and forceful responses to prevent the spread and provide adequate care. Added to this is the persecution of those who offer information or data. Deliberate schemes seek to maintain opacity even at the cost of the integrity of public workers who are willing to talk about the precarious working conditions.

What do we need to know?

Everyone has the right to ask and receive timely answers on issues of public interest linked to the Covid-19 pandemic, to make timely decisions and follow appropriate health recommendations to prevent the spread, as well as to exercise citizen control over the actions of the state.

On March 12, Espacio Público delivered a request for information to different health agencies on the coordination mechanisms to respond to the presence of the virus. In this regard, the organization asks for details about budget allocations for prevention and response, priorities, working criteria, the management of resources, and the number of tests available to diagnose the COVID-19 virus. It was also inquired about the mechanisms for collecting and disseminating data on the presence of the virus and the mechanisms for giving accurate information on risk, severity, progression, and treatment of the disease. The request for information must be answered in 20 business days.

What can we do?

Information is the main input for decision making. This becomes more evident in situations like the one we currently face. Today, accessing epidemiological data has implications for our health and the well-being of our environment.

The pandemic demands quality information. And this is a double challenge. The first is to stop the circulation of false information, which has been enhanced with the reach of the global computer network. The second, of a local nature, is to circumvent difficulties in communicating: unstable Internet, problems with the open television signal, and electrical blackouts.

Both challenges demand an active role on the part of citizens (users/consumers): each person can discern the content they receive and not spread information that they identify as false or suspicious.

To make this “content filtering” concrete, we recommend four actions that you can incorporate into your information routine (television, radio, newspapers where they exist; conversations; Internet): Stop, Doubt, Search and Cooperate.

STOP

False information aims to generate an emotional response that prompts you to spread it immediately, without thinking.

Does what you read, listen, or see surprise you, generate repulsion, indignation, alarm, a sense of danger? Take a minute to think beyond your emotional response. Especially in moments of effervescence.

Example:

Starting tonight at 11 PM no one can be on the street. Close doors and windows. 5 helicopters of the air force will spray disinfectant as part of the protocol to eradicate the coronavirus. Share this message.

Did you receive this message on WhatsApp through a family member or neighbor? A month ago this text would not have gone viral, but during quarantine in a complex humanitarian crisis, it plays with the hope of some. So far “there is no specific vaccine or antiviral medication to prevent or treat COVID-2019” according to the World Health Organization.

DOUBT

We must evaluate the information someone shares with us from a critical perspective. Ask yourself: what, who, how, when, where, and why, both in form and substance.

On the form: what am I seeing, hearing, or reading; who transmitted this information to me; how the information came to me; when was it passed to me and why / why do I receive this information.

On the substance: what happened, who is involved, how and when things happened, what were the causes and / or consequences.

SEARCH

Build the habit of investigating. The questions asked (in doubt) must be answered; Lean on the resources you have at hand, in the digital and the real world.

Is someone you know at the scene able to provide you with information for a moment? Is there someone in your environment familiar with the issue and able to provide true criteria?

Depending on the format of the content, you can help yourself with different digital tools that make it easy to check what made you hesitate.

For information on the Covid-19, refer to the World Health Organization and the Pan-American Health Organization websites:

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

https://www.paho.org/en/topics/coronavirus-infections/coronavirus-disease-covid-19

COOPERATE

Sharing your findings is necessary to counter misinformation.

Do not spread information that you identify as false and if you did, warn others when you find out that it was not true. Use for rectification the same means that you used in spreading the false content. To err is human, to rectify wise.

If you suspect that information is false and you cannot investigate, send it to the online verification teams that exist in the country:

Cazadores de Fake News (Fake News Hunters): https://cazadoresdefakenews.info/

Cocuyo Chequea (Cocuyo Fact-Checks): https://efectococuyo.com/category/cocuyo-chequea/ Email: chequea@efectococuyo.com

Es Paja (It is fake): https://espaja.com/ Whatsapp: 424-1981060

Observatorio Venezolano de Desinformación de la UCV (Venezuelan Observatory of Misinformation UCV): @ObserVeUcv @InfoPublicaVe

Cotejo (Fact-Check): https://cotejo.info/

Observatorio Venezolano de Fake News (Venezuelan Observatory of Fake News): https://fakenews.cotejo.info/ Email: observatoriofnredes@gmail.com