“It is the future of the whole civilized world which is at stake”. These were the words pronounced by the first Secretary-General of the United Nations, Trygve Lie, at the First Session of the General Assembly (February 1946) to summarize the aspiration for permanent peace for all the people on Earth after a bloody war.

I bring up those words because I feel that they describe perfectly the present and future of planet Earth, currently engaged in a relentless fight for the preservation of ecosystems that guarantee the survival of species, including us, Homo sapiens.

Through a variety of programs, the UN has taken on international leadership on climate change issues and the role of human beings in modifying the ecological balance.

What is climate change? To answer the question, I consulted Alicia Villamizar, an authority on the subject. Among other merits, Alicia is a professor at Simón Bolívar University and an elected member of the Academy of Physical, Mathematical and Natural Sciences where she has coordinated, since 2014, the very active Academic Secretariat for Climate Change. She has served for 20 years as a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a global authority on climate-related natural and social sciences.

“There are two complementary concepts of climate change, the scientific concept and the political concept,” Alicia tells me. The scientific concept refers to statistical variations in the climate over long periods due to natural or induced processes. The political concept is given by the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, whose Article 1, defines it as “a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods.”

Over millions of years, the Earth has been subject to global natural cycles of cooling (glaciations) or warming (interglacial periods) as a product of multiple factors. However, the current rate of warming is unparalleled in the planet’s geological history. This disproportionate increase in the average temperature of the planet, which does not correspond to a natural cycle, is caused by the accumulation of the so-called “greenhouse gasses.”

What are these gases? The scientific evidence on the subject is overwhelming in pointing to the emission and accumulation of “greenhouse gasses” as responsible for the increase in atmospheric temperature; that is, carbon dioxide (CO2), methane and nitrous oxide generated by human activity since the onset of the industrial revolution in the mid-18th century.

Measurements of CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere in the last 800 thousand years -until the beginning of the 20th century- indicate that they remained constant in the range of 170 to 300 parts per million, while the average temperature was also stable. Since then, humans have contributed around 50 billion tons of greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere, mainly from the use of fossil fuels (oil and coal), which have contributed to a current level exceeding 400 parts per million.

The average temperatures in the decade spanning from 2011 to 2020 exceeded those of any other decade of the previous 6,500 years, and now reveal a dangerous increase of 1.1°C, accompanied by droughts, floods, and frequent storms, which are dramatically affecting life on the planet.

What does the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) propose to stop this destructive course? The measures include the stabilization of the temperature increase below 2°C, for which it is essential to drastically reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to zero. If this is not achieved, the limit of 1.5°C established by the IPCC as the boundary between a dangerous and a catastrophic scenario, will be irremediably exceeded by 2030, while the threshold of 2°C will be reached by 2050.

Many international conventions have been signed since 1972, the year that marked the first Conference on the Human Environment, held in Stockholm under the sponsorship of the UN. This was followed by the 1992 “Earth Summit” in Rio de Janeiro, where the Climate Change Convention was agreed upon.

Since 1995, annual meetings have brought together political leaders, diplomats, scientists, media and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) from more than 190 countries to discuss ideas to reduce the impact of human activities on the climate. Usually, the meetings result in the signing of a new commitment or protocol, as well as renewed concerns whenever things turn out to not be progressing with the urgency demanded by the climate emergency that threatens us all.

A lot of money is involved in implementing climate agreements, albeit little will to achieve them, while time goes by without us getting closer to the zero emissions that could stop the increase of 2ᴼC in global temperature before 2050.

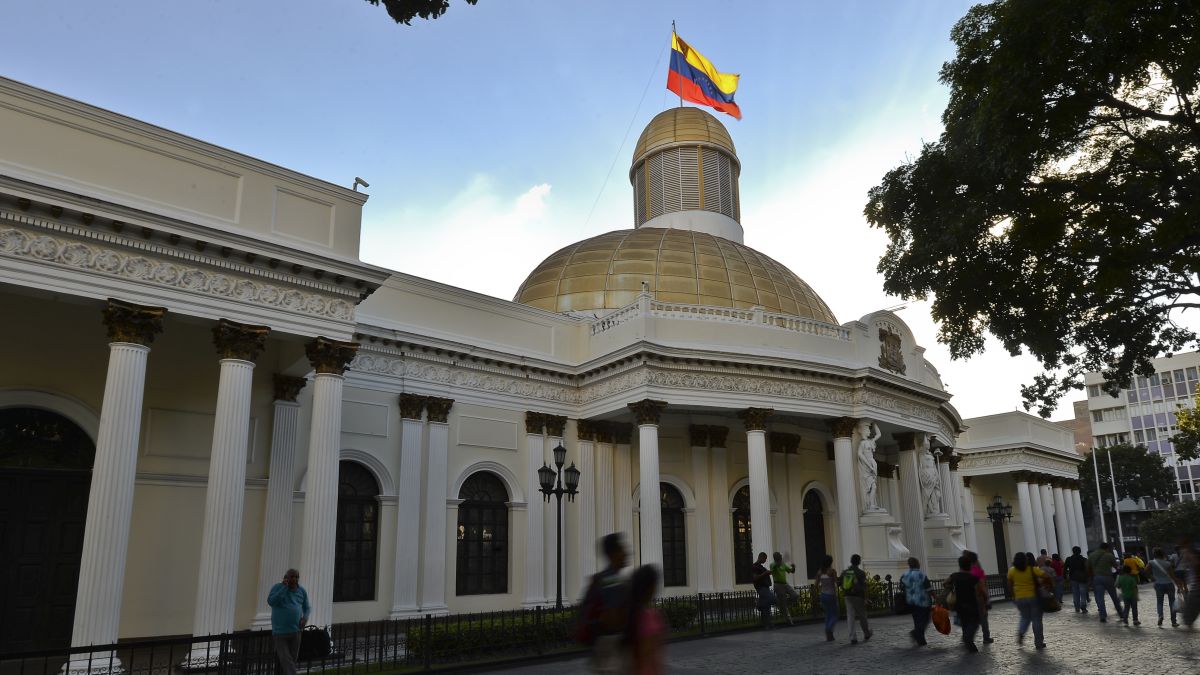

The impact of climate change in Venezuela

If things continue like this, a temperature increase between 2ᴼC and 2.5ᴼC will make most of the tropical belt of Latin America uninhabitable. The effect will be more severe in regions closer to the equator and the sea level, precisely where Venezuela is located.

Venezuela has a broad set of constitutional regulations on environmental issues (articles 127 et seq.), 28 laws, 55 executive decrees, 6 ministerial resolutions and 47 international instruments. These extensive regulations could give the impression that environmental matters are properly regulated.

However, according to the NGO Acceso a la Justicia, Venezuela is falling behind with respect to the different treaties and conventions developed at the international level and, more specifically, at the hemispherical level, with the creation in 2021 of a Presidential Commission for the Climate Change that has failed to bring initiatives to the field.

Alicia Villamizar directed me to the different documents published by the Academy of Physical, Mathematical and Natural Sciences through the Academic Secretariat for Climate Change under her coordination. The reports are very well documented, written by a group of around 60 Venezuelan researchers, whom I describe as unique in the country.

Especially relevant are the Academic Reports on Climate Change (the first report published in 2018, and the Second Report, currently in progress); Aportes para la Actualización de la Contribución Nacionalmente Determinada (NDC) de Venezuela para el período 2020-2030 (Contributions for the Update of the Nationally Determined Contribution of Venezuela for the period 2020-2030; 2023); Lineamientos para la actualización del Inventario de Gases de Efecto Invernadero del País (Guidelines for updating the Country’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory (in progress); Compromisos de Venezuela con el Acuerdo de París (Venezuela’s commitments to the Paris Agreement), Part 1 and Part 2 (2022).

These rigorous documents include topics related to climate change science, threats, vulnerability, adaptation and mitigation that should be used by the State agencies, private companies and society as a guideline in the implementation of actions to address Venezuela’s challenges.

In the presentation of the first draft of the Second Academic Report on Climate Change in Venezuela, the Academy recalled that Venezuela ranked 118 out of 166 in the 2022 Global Sustainable Development Report, a position that reflects the lack of a national framework of policies and strategies in the face of climate change and the lack of compliance with international agreements.

The reduction in the emission of greenhouse gasses documented in the country in the last decade is not the result of a policy aimed at this goal but the consequence of an economic crisis that has caused a decrease in power generation, the reduction in oil production and refining, and the drop in the production of steel, aluminum and cement.

According to the Venezuelan Observatory on Political Ecology, “as an oil and gas producer, Venezuela must initiate and step up the big shift towards a new development model that is not exclusively anchored to extractive industries; a less polluting model that is more compatible with the effective exercise of the human rights of present and future generations.”

Alicia Villamizar insists on explaining that “In Venezuela, we are more vulnerable and exposed to the impacts of climate change, to which is added the complex humanitarian crisis that configures a context of precariousness in all areas of the country.”

*Gioconda Cunto de San Blas has a Ph.D. in Biochemistry from the Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, Scotland, and a Chemistry degree from Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV). She is an Emeritus researcher at the Venezuelan Institute of Scientific Research (IVIC) and a member of the Academy of Physical, Mathematical and Natural Sciences (Acfiman).

Translated by José Rafael Medina