The official narrative first denies the facts and then blames others for them. Under this logic, blackouts are the product of sabotage, the migration crisis was induced, and the shortages of basic products were fabricated. After denying the crisis and shortages of 2016 and 2017, the propaganda apparatus now says that the stagnation of wages or the shortage of medicines in hospitals is due to the sanctions, which already existed but were not mentioned

“Amid the pandemic, the US has launched an attack against the Venezuelan economy that has also affected wages in the country. Who can deny the need to increase the salary? No one, the question is how much, and endless demagogy is unleashed from the right to the pseudo-left… They want to bankrupt the country to generate a disastrous crisis, and yet this government has done everything to guarantee no such unrest,” said the vice president of the Economic Commission of the National Constituent Assembly, Jesús Faría, on July 30, 2020, in justification of the delay in the increase of wages.

Faría stressed that the sanctions affected 95% of the country’s income. “We in the Government would like to set minimum wages at 300 dollars,” he assured without presenting supporting studies of the economic feasibility of the move. However, the Supreme Court of Justice also voided a law passed by the opposition-controlled National Assembly to increase the salary of public teachers in 2016.

Three years earlier, in an interview with Venezuelan TV station Globovisión, Faría had assured that Venezuela was recovering from the consequences of the economic blockade and explained that the sanctions had caused the country to lose “more than 140 billion dollars, which could have been invested in salaries, social security and public services.” Once again, a figure lower than the amounts denounced in recent corruption cases.

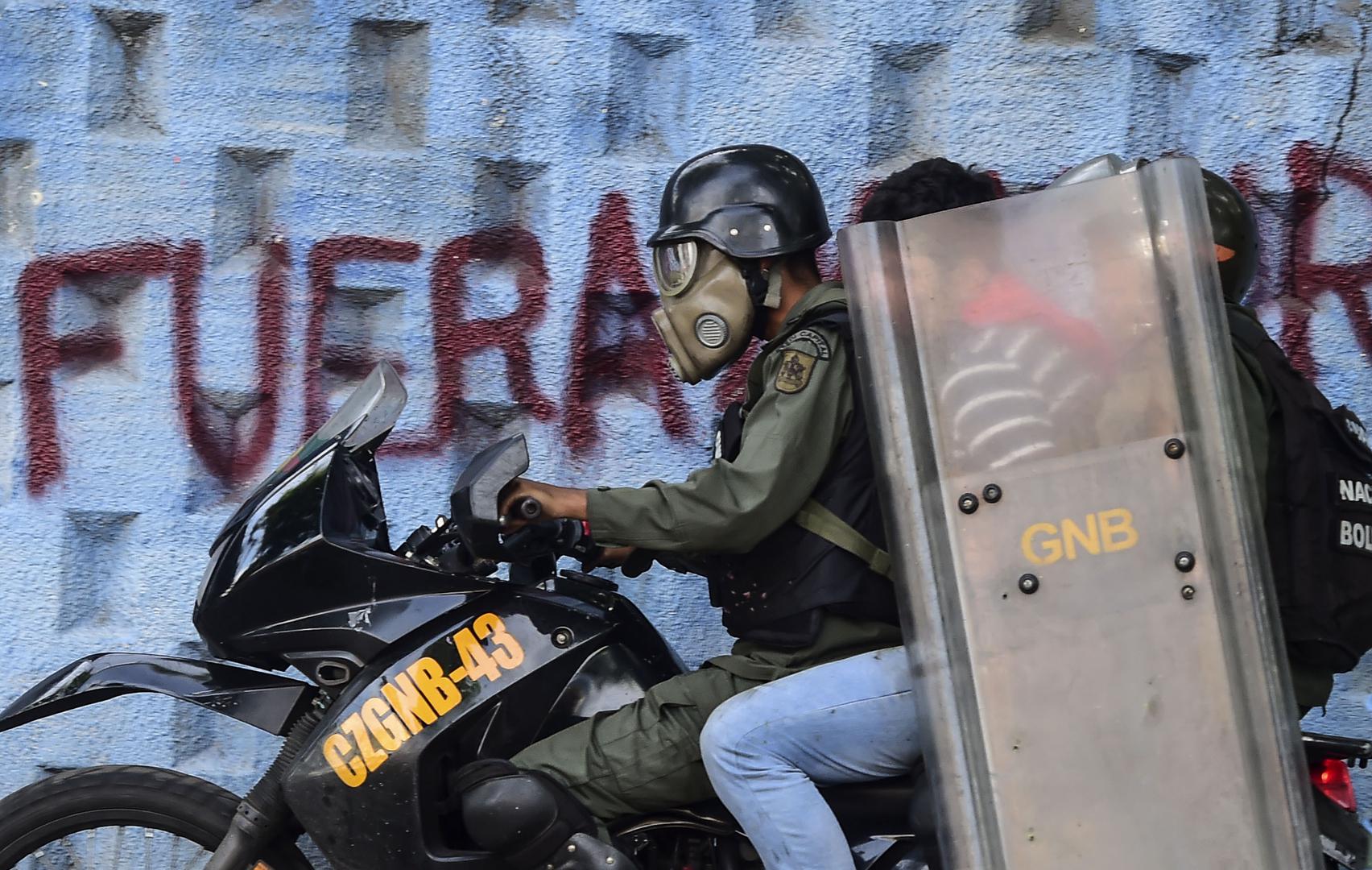

In the first half of 2022, a national wave of protests by teachers, doctors and public workers, retirees and pensioners demanding better wages and working conditions caused the Venezuelan state machine to resort to this old narrative to overshadow the demonstrations through an avalanche of messages used to divert attention or minimize labor demands.

C-Informa, a coalition made up of the Venezuelan media and organizations Cazadores de Fake News, Efecto Cocuyo, El Estímulo, Medianálisis and Probox, described how thousands of irregular Twitter accounts associated with the Maduro administration produced more than 160 million messages to try to obscure, or at least divert attention from, the demonstrations of civil society. In a previous installment, C-Informa had found that disinvestment and corruption were the cause for the sharp drop in oil production six years before the first economic sanction was signed by the Donald Trump administration.

According to a Probox analysis, the situation of the economy and wages became the predominant topic of conversation on Twitter in 2022, representing 72% of the messages written by Venezuelan users. During that year, teachers used hashtags like #SalarioJustoYa (“Fair wages Now”) to convene demonstrations, which were joined by other public employees as the government flooded the platform with propaganda.

“University professors are worse off than slaves (…) the salary is not enough for a day’s worth of food. After 25 years of work and 6 of retirement, my retiring allowance is 0.000035 Bs #SalarioJustoYa ”, tweeted José Villa, a professor at the University of Zulia (LUZ) in February 2022.

During 2022, the trends promoted by the Venezuelan Ministry of Communication and Information exceeded 167 million tweets, mostly related to official propaganda that blamed sanctions for the lack of better salaries. On the other hand, the protest of citizens online added more than a million messages. In other words, there were 166 propaganda tweets for every organic tweet of citizen demands.

In the first half of 2023, the disinformation machinery has not lowered the guard, nor have the protests of public workers, which numbered 602 as of May, according to the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict (OVCS), which ranked low wages as the main reason for public demonstrations.

In the advent of workers’ day, public sector employees fanned their demands on the streets and online with hashtags such as #SalarioDignoYSuficiente (“Living and adequate wages”), which gained notoriety after the official announcement of an increase in cash bonuses through the Homeland card that evaded a formal raise of the minimum wage, which has been fixed at 130 Bs since March 2022, roughly equal to 4.95 US dollars a month at the official exchange rate of the Central Bank of Venezuela as of May 2023.

The findings of the ProBox investigation show that people’s voice online was silenced in a sea of misinformation with hashtags such as #TrabajoYPatria (“Work and Homeland”), #LasSancionesSonCriminales (“Criminal Sanctions”) and #LasSancionesDestruyenElSalario (“Sanctions destroy salaries”), promoted by the Ministry of Information to overshadow and displace from the online conversation the appalling working conditions that have been dragging on for years, adding that “economic harassment destroys wages.” Ironically enough, even the “Twitter troops” used by the government have protested on the platform over the lack of payment.

The Fake News hunters team at Cazadores de Fake News used Meta’s Crowdtangle tool to track and analyze public content on Facebook and Instagram, identifying misinformation related to international sanctions and salaries in Venezuela.

One message on Facebook indicated that “sanctions induced a collapse that caused a stroke to the heart of the Venezuelan economy as the country’s most important resources and assets were frozen or withheld abroad.” This text is accompanied by an image entitled “The blockade in figures” showing the alleged “resources and assets of the Venezuelan government frozen or confiscated abroad.”

The infographic mentions “7 billion USD frozen in international banks”. However, the figure contradicts the information provided by government officials, who have spoken of 3 billion dollars.

In October 20202, executive vice president Delcy Rodríguez assured that the frozen funds amounted to 30 billion dollars, although she had previously endorsed the figure of 7 billion.

A problem of recognition rests at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Bank of England regarding the legitimate government of Venezuela. The doubt about whether power was held by Maduro or the interim government of Juan Guaidó paralyzed the transfers or granting of funds but the money is still available, for which it has not been confiscated but temporarily withheld.

On June 30, 2020, the British justice denied an appeal by the Maduro government on a ruling granting access to 30 tons of gold valued at 1.9 billion dollars to Guaidó’s interim government. However, given that the British government informed the Court of Appeal that it no longer recognized Guaidó or the 2015 National Assembly as the legitimate representative of the country after May 2023, the British justice ordered a trade court to decide on a course of action.

“The IMF’s commitment to member countries is based on the official recognition of the government by the international community, as reflected in the IMF membership. There is no clarity about the recognition at this time”. This was the main argument used by the IMF to reject the request of the Maduro government.

In the case of Citgo, a subsidiary of the Venezuelan public oil company PDVSA in the United States, although a new administrative board appointed by the 2015 National Assembly holds control of the company, fear prevails in Washington about a disorderly transfer of management of a company that remains in Venezuelan hands even though a judge had ruled on June 28, 2023, the resumption of the auction of stocks to honor the debts derived from the expropriations ordered by president Hugo Chávez.

The Venezuelan public TV channel VTV posted several messages between February and May 2023 that also blamed international sanctions for the economic crisis, including the sharp drop in wages.

Statistical silence to hide the crisis

When talking about the crisis in the health sector, the regime’s narrative has blamed different aspects of the sanctions, including the freezing of assets and the impossibility of negotiating with other countries, as the main reasons for the collapse of the medical care system.

In this regard, 4 Venezuelan propaganda outlets issued 8 posts on Facebook in 2023 and 5 posts on Instagram between May 2019 and April 2021.

On Instagram, the most viral post on the subject reached 16,049 views. It was shared by Venezuela-sponsored TV station Telesur on March 15, 2021, as part of a series of posts about a report by the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights, Alena Douhan.

With the video, the station pointed out that the withholding of Venezuelan assets in different international banks due to the sanctions is the reason for the healthcare crisis, expressed in an acute shortage of vaccines, medicines, reagents, and even a decrease in medical and health personnel that, all together, constitute a violation of the right to health. However, the claim ignores the reports, complaints, and studies documenting the fall in health indicators and operating conditions informed by the health workers themselves.

In this and other similar cases, the official propaganda omitted once again a crisis that started many years before the first sanctions as a result of public mismanagement.

A 2016 report by the Coalition of Organizations for the Right to Health and Life (CODEVIDA) and the Venezuelan Human Rights Education-Action Program (PROVEA) details that the availability of beds in public hospitals dropped from 30,964 to 20,821 between 2009 and 2014.

The document also warned of the loss of 6,700 doctors in the public health network, according to figures from the Venezuelan Medical Federation, equivalent to 24% of the workforce of the sector, 30% of resident doctors and 60% of nursing personnel. According to the report, this occurred due to restrictions on medical practices, the violation of labor rights, and hostility and insecurity in health centers, which range from robberies and assaults on the staff to surveillance by pro-government activists.

The 2012 annual report of the Ministry of Health also recorded a drop in emergency care beds between 2011 and 2012, which led to more than one million unattended patients.

Likewise, a review of the figures for international trade on the website of the National Institute of Statistics reveals a dramatic drop in the purchase of medicines and surgical supplies as of 2013, even though oil production remained high until 2015 and the first sanctions on the oil sector were instilled six years later.

The data reveals that the purchase of pharmaceutical products reached a peak in 2012 with just over 3 billion dollars, dropping to just under 2 billion in just three years. In 2017, the figure reached just 675 million dollars, an 80% fall.

On the other hand, the National Survey of Hospitals, carried out by the Médicos por La Salud network in 130 hospitals across 19 states of the country since 2014, documented a “serious or absolute” shortage of medicines in 55% of hospitals, which rose to 76% by 2016. Medical-surgical material is also prone to shortages, which rose from 57% in 2014 to 81% in 2016.

Once again, the origin of the problem is related to previous circumstances such as the price and distribution control system that affected both the production and supply of medicines, as well as corruption and bureaucracy in the foreign purchases system, which was relaunched for the third time in early 2014 before being definitively suspended in 2016. Four billion in debt to international suppliers led to the paralysis and reduction of the pharmaceutical industry and the domestic market as several production deals with countries like Portugal, Cuba and Colombia never materialized.

Likewise, the allegations of the granting of public funds to relatives and friends of the directors of the Venezuelan Social Security Institute for the purchase of high-cost medicines for chronic diseases and hospital repairs exceeded one billion dollars according to investigations by Runrunes and Transparencia Venezuela. The 2013 report of the Office of the Comptroller General revealed hundreds of contracts that were not executed or supervised, administrative irregularities, and the acquisition by the Ministry of Health of just 0.83% of the medicines needed in the country.

The figures also show a picture of the deterioration of the healthcare sector in Venezuela years before the sanctions, including data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), Unicef and the World Bank.

The abandonment of the farming of cereals after 2008 was the prelude to a drop in the consumption of plant and animal protein by Venezuelans and the increase in malnutrition and neonatal, infant and maternal mortality.

A study published in the scientific journal The Lancet found that infant mortality had risen 40% between 2008 and 2016, as well as cases of HIV, malaria and measles after a systematic drop in prevalence since the 1950s.

The two-year statistical silence of the Government tried to hide the inevitable consequences of this perfect storm. But when the Epidemiological Bulletins for mid-2015 and 2016 were published, the truth came to light: infant and maternal mortality had skyrocketed, as well as malaria cases. The revelation led to the dismissal of Minister Antonieta Caporale and national and international reactions of concern about an impending humanitarian crisis.

In 2016, the Venezuelan Pharmaceutical Federation (Fefarven) warned that government policies had led to an 80% shortage of medicines, forcing Venezuelans to take to social media in search of donations or exchange of medications, under the hashtag #ServicioPúblico (“Public Service”) on Twitter and Facebook.

In 2022, Venezuelan civil society and healthcare workers protested the deficiencies of the public health sector in Venezuela and the availability of medicines, with the use of hashtags such as #HagamosRuido (“Let’s make noise”) and #CrisisHospitalaria (“Hospital Crisis”) that accounted for over 17,000 tweets.

The statements by Carlos Rotondaro, chairman of the Venezuelan Institute of Social Security (IVSS) for 10 years and Minister of Health between 2009 and 2010, are a clear example of how the narratives about the humanitarian crisis or the sanctions have been presented under a post-truth logic, the same as the shortages or the migration crisis: the existence of the situation is initially denied but later recognized and blamed on external factors.

In mid-2017, Mr. Rotondaro denied the existence of a humanitarian crisis and called the shortage of high-cost medication and cancer drugs “intermittent” and soon to be solved thanks to the State’s response capacity.

Less than two years later, now a refugee in Colombia and under investigation by the Maduro regime, the former official recognized what journalists, workers and unions had denounced for years: the delay in the allocation of funds for the purchase of medical supplies responded to “indolence”, and accused the Minister of Health, Luis López, and the Minister of Labor, Francisco Torrealba, for giving the order to “hide the medication” for chronic patients in times of elections.

During an interview on TV in July 2017, the head of the Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Observatory, William Castillo assured that “there was no humanitarian crisis” in Venezuela; there was instead a conspiracy by businessmen and the media to “conceal the products” to force people to queue for food and medicines. He also assured that the fall in the national income was a symptom of global problems and that the country was receiving large investments such as the construction of a national railway network, a project that remains completely abandoned today.

The propaganda apparatus fails to hold up when contrasted with official reports from the National Institute of Nutrition and different experts who exposed the increase in infant mortality, malnutrition and obesity in 2016 as a consequence of government policies that sought to improve the availability and affordability of food, without combating a greater preference for sugary products and carbohydrates that caused a combination of overweight and malnutrition.

In early 2018, Cáritas and Unicef warned that 20% of newborns were at risk of malnutrition. But this was not something new: 15.5% of babies already showed problems in 2014, when dozens of newborn deaths were reported in hospitals across the country due to electrical blackouts and poor sanitation.

The sharp rise in cases of HIV, measles and malaria, neonatal deaths, and deaths derived from prolonged blackouts and the shutdown of medical services due to equipment failures, lack of water supply and the mass resignation of health workers, expose the systematic failure of the policies of harassment and persecution, neglect, corruption and embezzlement that were consistently denied until the sanctions served as a scapegoat for the well-oiled State propaganda machinery.

Translated by José Rafael Medina